BrightnessGate for the iPhone & Android Smartphones and HDTVs

Why Existing Brightness Controls and Light Sensors are

Effectively Useless

Wasting Lots of Energy and Battery Power,

Reducing Screen Readability, and Causing Eyestrain

Dr. Raymond M. Soneira

President,

DisplayMate Technologies Corporation

Copyright © 1990-2010 by DisplayMate Technologies Corporation. All

Rights Reserved.

This article, or any part thereof, may not be copied,

reproduced, mirrored, distributed or incorporated

into any other work without the prior written permission of

DisplayMate Technologies Corporation

This article is Part II of an article series on the iPhone 4 Retina

Display,

the Samsung Galaxy Super AMOLED Display, and the Motorola Droid.

Overview

Although consumers currently don’t pay

much attention to them, the Automatic Brightness control and Light Sensor on

smartphones and HDTVs has a major impact on displayed image quality, screen

viewability and readability, as well as preventing eye strain and headaches

when the screen is too bright or too dim for the current level of ambient

lighting, which varies considerably. But for many consumers, organizations and

even governments, it is their impact on power consumption that generates the

greatest concerns and emotions. Most smartphones and HDTVs run with the screen

considerably brighter than it should be, which wastes a lot of power in addition

to causing eyestrain. On smartphones the display can use as much as 50 percent

of the total phone power, which has a major impact on the phone’s running time

on battery – a big concern for all users. On HDTVs the display can use as much

as 75 percent of the total TV power, which can be over 200 watts. Since there

are 330 million TVs in the US, and they are on over 600 billion hours per year,

that adds up to a considerable amount of wasted energy, money, and oil – so

even federal and state governments get concerned… And there are other important

benefits to reducing display power – it lowers the internal heat and

temperature of both smartphones and HDTVs, which reduces component aging,

failure rates and repairs. But for all of its advantages Automatic Brightness

still needs to properly control the screen brightness over the very wide range

of ambient lighting, otherwise the consumer will disable it and just park the

brightness close to maximum. Unfortunately, that is what happens most of the

time – here’s why…

From the above discussion, you would

think that a properly functioning Automatic Brightness would be a big deal in

the design, engineering, and marketing of smartphones and HDTVs – since they

are extremely competitive, especially the battery run time on smartphones, plus

every manufacturer is claiming to be environmentally “Green.” As we will

demonstrate below with extensive lab measurements for smartphones (and HDTVs in

a later article) this is instead a sham of incredibly poor design and engineering

– with Automatic Brightness in a great majority of smartphones and HDTVs being

effectively useless. And because they don’t work properly consumers simply turn

them off altogether, making matters even worse for power use, screen

readability and viewing comfort. This deserves to be called BrightnessGate – a

scandal with several causes…

You’re wondering how this could

possibly be the case – it’s because Automatic Brightness is being treated by

manufacturers as just a marketing feature for brochures and spec sheets (and

cursory Energy Star operating cost estimates for HDTVs). As a result it isn’t

given the engineering attention and expertise that it needs in order to

function properly and effectively, so that it is actually useful, and then

actually used by consumers – this latter point is the only one that matters!

It’s the Rodney Dangerfield function of smartphones and HDTVs because it “gets

no respect.” This article will show you why that needs to change…There are many

problems that need to be corrected – some are in the Automatic Brightness

control software and its user interface, which can be fixed with downloadable

updates, and some have to do with the light sensor, which will have to wait for

the next generation of smartphones and HDTVs. We’ll also outline how a fully

functional Automatic Brightness should work, including an interactive user

interface that adapts automatically to the user’s personal screen brightness

preferences. That is the key to its future success and to gaining the respect

and appreciation of consumers, manufacturers and even governments.

How Automatic Brightness

Works – In Principle

Both smartphones and HDTVs have a light

sensor located in the bezel right next to the screen that measures the ambient

light together with control software that appropriately raises or lowers the

screen brightness based on the measured light level. If you are watching in the

dark the screen should be appropriately dim. When the ambient light level is

higher the screen needs to be made appropriately brighter for two reasons:

because of glare from ambient light reflected off the screen, which washes out

the image, and because the eye’s light sensitivity decreases substantially as

the ambient light level increases. Unfortunately, none of the above currently works

properly in smartphones and HDTVs for the following reasons:

The Light Sensor

In a smartphone the light sensor is

facing your head and is measuring the brightness of your face instead of the

ambient light level that is behind and to either side of the phone, which is

what actually sets your eye’s light sensitivity and what should be determining

the brightness level of the screen. Similarly, in HDTVs the light sensor is

measuring the light level behind the TV viewers instead of the light that is

behind and on either side of the TV, which again determines the eye’s light

sensitivity level. The existing front facing light sensors are good for

measuring and correcting the image for glare from screen reflections (by

modifying the display transfer functions), but not for setting the screen

brightness. To do that in both smartphones and HDTVs a rear and side facing

ambient light sensor with a different angular profile than the current

Illuminance sensors is needed for future hardware designs. Note that a front sensor

for glare is not as important since screen reflectance can be very low – around

5 percent for many smartphones and HDTVs – see Part I of this

article.

Automatically Adjusting

the Brightness

The screen brightness

needs to be set carefully and systematically based on the data from the light

sensor. Here the smartphones and HDTVs fail again with poor and even bizarre

behavior that we document below. Another sign of careless engineering – all

three of the smartphones that we tested have operational bugs or errors with

their Automatic Brightness. One essential feature missing from both smartphones

and HDTVs is allowing users to interactively adjust the display for their own

visual preferences on how the screen brightness should vary as the ambient

light changes – and it should be accomplished automatically as we’ll outline

below. Some people and applications prefer a brighter or dimmer screen, and

some people are willing to put up with a dimmer screen that may not be as easy

or comfortable to read – in return for longer battery running times. So it’s

important to implement a properly functioning Automatic Brightness that

automatically adapts to the user’s own brightness preferences – otherwise it

will be disabled by the user.

Results Highlights

Here are the main results from our

extensive labs tests and viewing tests on three smartphones that we performed

to evaluate the Automatic Brightness Controls and Light Sensors under a wide

range of ambient lighting conditions.

Determining the Optimum Screen Brightness

The first step in evaluating Automatic

Brightness is to determine how the screen brightness should change with ambient

light level for optimum viewing. To demonstrate the proper relationship I read

an article from the New York Times on the iPhone 4 under a wide range of

ambient lighting conditions. I turned Auto-Brightness Off and then manually

adjusted the screen brightness for my own optimum viewing comfort – not too

dim, not too bright, just right – for each of 7 different ambient light levels,

from total darkness up through moderate outdoor lighting levels. After each

reading I measured the Ambient Light Brightness (Illuminance in lux) and the

screen’s Brightness (white Luminance in cd/m2). The results appear

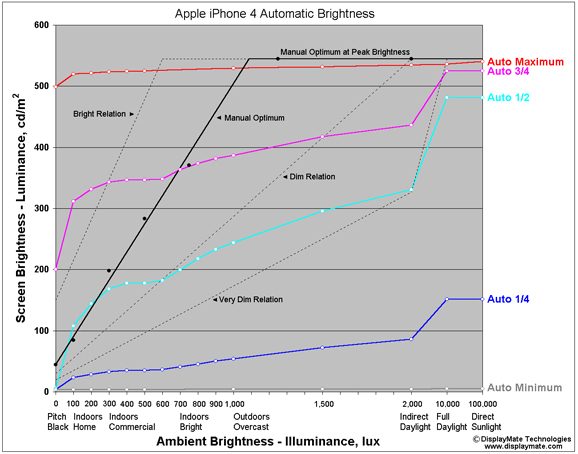

as the black data points in Figure 1 along with a solid black trend line. At about 1,000 lux (which is at the low end of

outdoor lighting levels) I reached the maximum screen brightness for the iPhone

4, which is 541 cd/m2 – it is the brightest mobile display I have

ever measured, but above 1,000 lux the iPhone 4 can’t provide as much screen

brightness as I would like to have. The screen is still readable well beyond

10,000 lux (which is full daylight that is not in direct sunlight) but it gets

increasingly hard to comfortably make out the contents of the screen at the

higher ambient light levels.

The optimum screen brightness values

will vary due to personal preferences, and also with screen size and viewing

distance, but the proportional linear increase with ambient brightness

indicated by the solid black line in Figure 1 should be similar for everyone.

The dashed black lines in Figure 1 also show a wide range of alternative

brightness relations – the dashed lines labeled Dim and Very Dim are for

aggressive power savings at high ambient lighting or for people with more

sensitive eyes, and the Bright relation is for people or applications that need

particularly high screen brightness with ambient light. We’ll explain how to

automatically implement all of this functionality below. Now let’s look at the

Apple iPhone 4 and two Android phones (Samsung Galaxy S and HTC Desire) to see

how they perform…

Figure 1.

The measured Screen

Brightness for various measured Ambient Brightness levels. The manually

determined optimum brightness settings are the black data points with their

trend line. The values for five different Auto-Brightness slider settings of

the iPhone 4 are labeled Auto Minimum to Maximum. Circles are the data points.

The dashed lines show a wide range of alternative brightness relations. The

graph is linear from 0 to 2,000 lux and then jumps in steps to 10,000 and

100,000 lux. The labels from Pitch Black to Direct Sunlight roughly identify

the lux levels associated with them. The maximum Luminance of the iPhone 4 is

541 cd/m2.

iPhone 4 Auto-Brightness

Next, I turned Auto-Brightness On and

then measured the screen brightness (white Luminance cd/m2) that the

iPhone 4 produces under a wide range of ambient light levels, from 0 lux (Pitch

Black) up through 100,000 lux (Direct Sunlight). When Auto-Brightness is turned

On the Brightness slider adjusts the Auto behavior to allow consumers (in

principle) to set their own individual screen brightness preferences for

ambient light. To evaluate this, I measured 5 different settings of the slider:

Maximum, ¾, ½ (center), ¼ and Minimum. The results are plotted as the colored

lines in Figure 1 – the circles are the measured data values. None of the Auto

Brightness settings even remotely approaches the desired behavior discussed

above. It certainly looks as if no one at Apple ever bothered to set or check

Auto-Brightness for useful performance, which is why there are lots of user

comments questioning how it works on the web… This is BrightnessGate for the iPhone…

The iPhone 4 comes from the factory

with the Brightness slider set to ½ (center) and with Auto-Brightness turned

On. At 2,000 lux, where just about everyone will want the display operating at

maximum brightness, Auto-Brightness sets it to only 60 percent of maximum, so

Auto-Brightness is throwing away 40 percent of the precious brightness needed

for screen visibility. And at 10,000 lux, which is full daylight, the screen

brightness is still below 90 percent of maximum. The ¾ setting is much too

bright and power wasteful for all indoor viewing and yet it still throws away

20 percent of the screen brightness at 2,000 lux for outdoor viewing. The

Maximum setting is useless because it varies the screen brightness (and power)

by less than 10 percent and the ¼ and Minimum settings are far too dim to be

useful for humans.

The iPhone 4

Auto-Brightness performs in a bizarre fashion where it typically makes the

screen too bright at lower indoor ambient light levels (which is important for

saving battery power) and too dim at higher outdoor levels (which is important

for screen readability) – it’s always wrong, usable but very inefficient and

wasteful. But BrightnessGate for the iPhone gets even worse…

iPhone 4 Auto-Brightness

Bug

One behavior of the iPhone 4

Auto-Brightness that is a serious operational error or bug is that it locks

onto the brightest ambient light sensor value that it has measured at any point

starting from the time it was turned on, and then continues to use that highest

value indefinitely to set the screen brightness until the display turns off –

either by cycling through sleep mode or full power off. This means that the

screen brightness is frequently set too high, which wastes power and can cause

eye strain if you move to lower ambient light levels. Auto-Brightness should

always follow the current ambient light level (with appropriate time averaging

and filtering). Apple should correct this with a software update. To easily

verify this behavior with your own iPhone turn On Auto-Brightness under

Settings and set the Brightness slider near the middle of its range. Go to a

very dark location. Click the sleep/wake button on the top of the phone to turn

the display off. Then wake it up with the sleep/wake button or the Home button.

Note the screen brightness in the dark. Now take the phone to a very bright

outdoor location (such as in direct sunlight) then go back (with the display

on) to your original dark location and monitor the screen brightness. The

display will remain at very high brightness indefinitely until the iPhone

enters sleep mode again (or runs out of battery). What’s even more shocking is

that BrightnessGate

is even worse on Android phones…

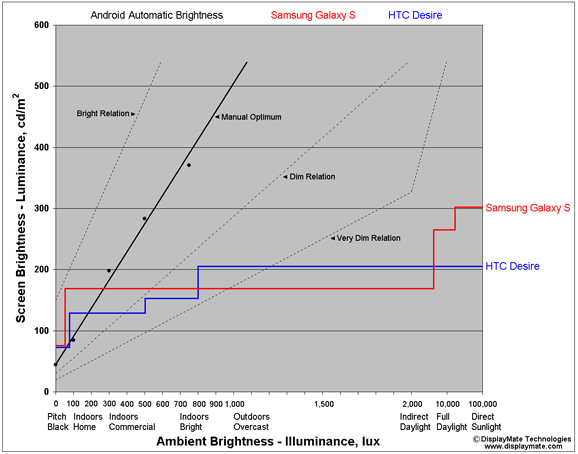

Figure 2.

The measured Screen

Brightness for various measured Ambient Brightness levels for the Samsung

Galaxy S and HTC Desire. The Manual Optimum relation and other elements are the

same as in Figure 1.

Android Automatic

Brightness

There are currently a large number

smartphones running Google’s Android OS, and all of the models that we have

looked at appear to work in the same way. There is a slider for manual

adjustment of screen brightness, but when Automatic Brightness is enabled the

slider disappears and there aren’t any user settings or preference adjustments

(unlike the iPhone 4) – you get whatever screen brightness settings Android and

the smartphone manufacturers have pre-programmed into them. Unfortunately,

those Automatic Brightness settings are incredibly primitive and crude – on the

Samsung Galaxy S and HTC Desire that we lab tested Automatic Brightness

produces only four fixed screen brightness levels when the ambient lighting

changes from pitch black all the way up to direct sunlight, with each

manufacturer setting their own breakpoints as shown in Figure 2. For this

reason alone, Auto Brightness is effectively useless for Android. But BrightnessGate on

Android gets even worse…

Android Automatic Brightness Bugs

Both of the Android phones we lab

tested have their own Auto Brightness operational errors or bugs. On the

Samsung Galaxy S two of the four Android Automatic Brightness levels are set

ridiculously high: 7,000 and 30,000 lux – they are about a factor of 10 too

high to be useful. The Galaxy S screen brightness remains at an incredibly low

170 cd/m2 up until near Full Daylight, only about 50 percent of the

screen brightness that it can deliver, and it waits up until almost Direct

Sunlight to move up to it’s maximum screen brightness of 305 cd/m2.

Since there are no available settings or adjustments it’s better to leave the

Automatic Brightness permanently off until this gets fixed with a software

update. The HTC Desire has a somewhat better choice of brightness level

breakpoints than the Galaxy S, but it has a bug similar to the iPhone – once

the light sensor detects a light level over 100 lux it won’t allow the screen

below Android brightness Level 2 until the display is cycled off by going into

sleep mode using the power button or Screen timeout.

Conclusion for the Current

Auto Brightness

Automatic Brightness on existing

smartphones is close to functionally useless because the manufacturers have not

made the effort required to develop, evaluate and test the software and

hardware so that they work properly and effectively. All of the models we

tested also have serious operational errors and bugs indicating how little an

effort has been made to make them work (or rather not work) properly. It’s

clear that most manufacturers are using ad hoc implementations instead of

methodical science and engineering, which is shameful and shocking… As a result

most smartphones are operating without Auto Brightness because consumers

disable them when they don’t work properly, which means the screen brightness

is seldom set correctly for the wide range of ambient lighting conditions that

most smartphones experience. It also means that the display is very likely set

by the consumer to a perpetual high screen brightness. As a result the battery

runs down much sooner than if the brightness and power were actively and

intelligently managed automatically, as they should be. We outline how to do

that next…

How Automatic Brightness

Should Work

There is one more thing… to make this

work smartphones and TVs need a convenient brightness control to tweak and

train the Automatic Brightness. Every TV and smartphone in the solar system has

a convenient Volume Control but in most cases you have to go down a couple of menu

levels to get to a cumbersome Brightness Control. My suggestion for all

smartphones: temporarily shift the Volume buttons to Brightness buttons by

pressing both the + and – buttons at the same time – which will activate a

temporary Brightness Shift. It’s fast, convenient and easy, and then have them

automatically time out and shift back to Volume Controls when you’re done

adjusting the brightness. This same suggestion applies to TV remote controls –

use a shift button to temporarily convert the Volume Control buttons into

Brightness Control buttons. Every display needs a convenient external

Brightness Control – not buried under several levels of menus. In all cases

it’s best to implement it using the existing Volume Control together with an

appropriate shift button.

The above is guaranteed to work nicely

and conveniently for all consumers, solve BrightnessGate, maximize viewing

comfort, screen readability, energy efficiency and battery run time all

together. For HDTVs it will lower your electric bill and even make a dent in

oil imports… I hope the manufacturers are listening…

Special Thanks to Jay Catral and Konica Minolta Sensing

for their instruments and technical support. To measure the Ambient Light Brightness (Illuminance in lux) we used a Konica

Minolta T-10 Illuminance Meter and for screen Brightness (Luminance in cd/m2)

we used a Konica

Minolta CS-200 ChromaMeter.

About the

Author

Dr. Raymond Soneira is President

of DisplayMate Technologies Corporation of Amherst, New Hampshire, which

produces video calibration, evaluation, and diagnostic products for consumers,

technicians, and manufacturers. See www.displaymate.com.

He is a research scientist with a career that spans physics, computer science,

and television system design. Dr. Soneira obtained his Ph.D. in Theoretical

Physics from Princeton University, spent 5 years as a Long-Term Member of the

world famous Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, another 5 years as a

Principal Investigator in the Computer Systems Research Laboratory at AT&T

Bell Laboratories, and has also designed, tested, and installed color

television broadcast equipment for the CBS Television Network Engineering and

Development Department. He has authored over 35 research articles in scientific

journals in physics and computer science, including Scientific American. If you

have any comments or questions about the article, you can contact him at dtso.info@displaymate.com.

About

DisplayMate Technologies

DisplayMate Technologies specializes in

advanced mathematical display optimizations and precision quantitative and

analytical scientific display manufacturer calibrations to deliver outstanding

image and picture quality and accuracy while increasing the effective visual

Contrast Ratio of the display and producing a higher calibrated brightness than

is achievable with traditional calibration methods. This also decreases display

power requirements and increases the battery run time in mobile displays. Our

scientific optimizations can make lower cost displays look almost as good as

more expensive higher performance panels. For more information on this

technology see the Summary description of our Adaptive Variable Metric

Display Optimizer AVDO. If you are a display or

product manufacturer and want to turn a standard panel into a spectacular one Contact DisplayMate Technologies

to learn more.

Article

Series Link: Display Technology Shoot-Out Article

Series Overview and Home Page

Copyright © 1990-2010 by DisplayMate Technologies Corporation. All

Rights Reserved.

This article, or any part thereof, may not be copied,

reproduced, mirrored, distributed or incorporated

into any other work without the prior written permission of

DisplayMate Technologies Corporation